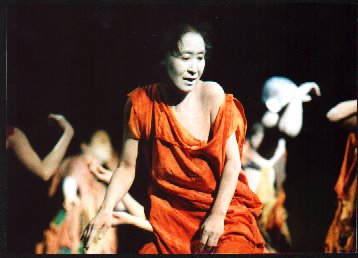

The performance of Kayo Mikami is really

wonderful. Its image is so beautiful. Her acting is perfect. Each movement of

her legs and arms mesmerized us. This is performance is incredibly marvelous.

The performance of Kayo Mikami is really

wonderful. Its image is so beautiful. Her acting is perfect. Each movement of

her legs and arms mesmerized us. This is performance is incredibly marvelous. The performance of Kayo Mikami is really

wonderful. Its image is so beautiful. Her acting is perfect. Each movement of

her legs and arms mesmerized us. This is performance is incredibly marvelous.

The performance of Kayo Mikami is really

wonderful. Its image is so beautiful. Her acting is perfect. Each movement of

her legs and arms mesmerized us. This is performance is incredibly marvelous.

iFranceuLfest RepublicanvRachel VALENTIN 29 Jun 1993j

All the movements developing on the stage surprise us ,amuse us, move us, and astonish us. All these feelings are brought to us at the same time.ccan old axiom is really hidden in the lines of her body intentionally distorted, that is you can come to see something unexpected when you fix your eyes on what is very close to you, or you can notice something large when keep watching simple , or you can something large when you keep watching something small. That is what we callgA Golden Axiom of Arthcc @

@@iRussiauPermiv16 Jun 1994j

@

@

@

Kayo Mikami succeeded in creating clearly and strongly a sense of passion and salvation throughout the performance. All the parts of this performance have their own vivid images.

iU.S.A.uNew York TimesvJannifer DUNNING .21 Nov.1994j

@By Marcia B.Siegel@

@@Kayo Mikami

Torifune Butoh-sha

La MaMa E.T.C.

November 10 through 13

Japanese Butoh dance is a kind of body spectacle, and Kayo Mikamifs Kenka (Consecration of Flowers) seemed a perfect balance between introversion and flamboyance. It also renewed my interest in Butoh, which, 15 years after it was first seen in America, seems to get more formulaic without getting any advertent sign of an inner impulse. Unlike American modern dance, feeling isnft physicalized or dramatized. When Mikami begins to vibrate with extreme tension, shefs not describing any emotional state, but rather burning off the waste products of a captive rage.

Kenka, basically a solo, has seven descriptively titled sections that could refer to stage in a life cycle, from the ancestral world to earthly existence and back again to the spirit plane. But that makes the piece sound more narrative than it is. What I remember are only the repetitious efforts of each step. It take her 10 minutes to get across, move downstage, then retrace her path. A ghost, I think, condemned to journey forever in the body of a human.

She appears in a red dress, walking almost primly but occasionally sinking down, her pelvis swinging oddly, seductive yet grotesque. An elephant dreaming shefs a fish.

Two hairless, nearly naked men throw themselves into the space in violent tantrumy bursts, then squiggle around close to the floor.

An astonishing, syncretic soundtrack plays a combination of East Indian, Chinese, Turkish, and Latin rhythms, each one distinct but blended with the others. (Original music was credited to J.A.Seazer)

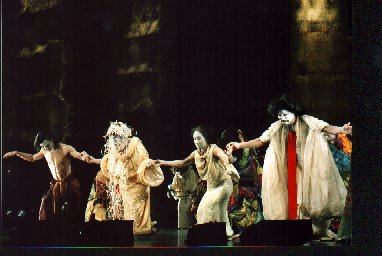

Mikami heaves into the space in an amazing, spiky structure resembling an African body mask, which covers her like a portable hut. It can stand by itself, and the two men come out and poke at it. They lift it high in the air, tilting it forward to show some decorative carved shapes, vaguely Indonesian, fixed on the top. Is this object Mikamifs home? Her altar?

The bald tumblers reappear, moving as if their bodies were splintered in tiny pieces. The woman arrives wearing high clogs with curved soles, and holding springy wands in her hand. The men take the wands and all three of them walk very slowly, calmly, forward and back, waving the wands up and down. When they get close to the audience, you see that the womanfs face is now covered with warts, but she isnft grimacing in pain or anything. Her expression is blank, untroubled.

At last, with gAmazing Gracehplaying in the background, a curtain opens to the top of the grass masked shapes that bring to mind the gods on a Buddhist temple. Moving more slowly than ever, the woman more rises and sinks. I think shefs verging on some unattainable stasis\always never quite there.

(U.S.A. Village Voice ,Marcia B.Siegel, 1994.Nov.)

ccKayo Mikami succeeded in portraying the revelation of the essence of her art in the same way as Borges portrayed its acquisition in his novel El AlephiThe method he uses is the creation of a manifestation of the infinity existing behind words as a finite mediumj

iSpainuEL CORREOvRosalia GOMEZ. 8 Jun.1996j

@

EL CORREO DE ANDAUCIA June 8, 1996

THE HUNDREDS OF FORMS OF KAYO MIKAMI

Rosalia Gomez

It has been always the motivation and mission of all kinds of arts to reveal and express what is intangible like spirits, souls or sentiments that lie behind what is tangible in this earthly world. Although the efforts of those artists who aspire to fulfill this ultimate goal are rarely rewarded with a complete attainment and appreciation, some blissful moments momentarily (and always momentarily) visit the performers as well as the audience.

The very thing was achieved by a Japanese dancer Kayo Mikami through her Butoh dance performance "Kenka or the Consecration of the Flowers" at the Central Theater Thursday evening. Following the methodology invented by Jorge Luis Borges in his El Aleph to express the infinite through the finite - called discourse, Mikami succeeded to reveal the essentials beyond the earthly phenomena by means of her bodily movements accompanied with her extravagant costumes and dexterous stage lighting.

The first part "A Phantom of a Woman Carrying her Own Baby" depicts a motherwho had killed herself and felt so sorry in the ethereal sphere for her baby left on the earth. Therefore she seriously wishes to meet with it and go thither and hither between the two worlds. Her toes grasp the earth, her body and arms crawl on the ground and her fingers point to the heaven above.

The audience were so astounded with the spectacle that they continued to be involved in the stage when Mikami, now clad in a red0kimono, reappeared as A Serpent Decorated with Bells and danced convulsively and frantically for liberating and conjuring up the gods positive energy towards the earthly people.

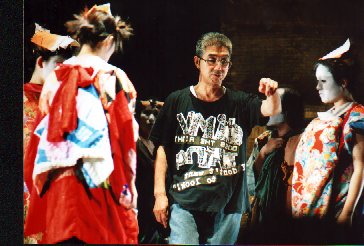

The whole performance named "Kenka" is a piece of work concerning the death and the ethereal world, composed, directed and choreographed by Mikami herself together with her husband Yukio Mikami, and collaborated with other three dancers of Butoh school.

Butoh, a school of experimental Japanese avant-garde dancing was originally founded by the late Tatsumu Hijikata based on the actual movements of Japanese pre-modern peasants. Kayo Mikami who studied in the school as one of his direct apprentices inherited his legacy practically as well as theoretically and is going farther beyond the frontier cultivated by her maestro. She affirmed the basic function of arts is always in searching of an alternative concept other than what we already had.

The audience of the Central Theater, Seville, were completely overwhelmed by the movements and facial expressions of the dancer from Japan. Also they were madereassured the furthest front of the present performing art is not in realism but in fictitious surrealism.

@

@

@

BUTOH DANCE 0OR THE CONTROL OF THE MOVEMENTS

This is the third time for us to appreciate Butoh dance in Seville which impressed us so with its intensified originality. At the opening it seem rather monotonous with its slow movements of the dancers. However, we gradually realize the crawling movements completely controlled by their marvelously refined technique are an inevitable prelude to induce us to the dynamism of Butoh dance into its climax.

In the pitch-darkness there is a coffin on the left-side of the stage. Out of the coffin something like ether vaguely comes out. Then it takes a shape like a ghost-woman, who is trying to hold her own baby and moves across the stage from left to right. After that nothing happens for nearly minutes. Therefore our expectations are somewhat betrayed. However we gradually understand this is an intentional interval to strengthen the dramatic anticipation. Still we are left in the complete blackness. A slight streak of light is projected to make a melancholic atmosphere on the stage.

Kayo starts to move without any visible motion as if she were like a still life in a play. Her slowness persuasively tells us how the heroine is tormented mentally and physically. There nothing there but her well-trained body dexterously controlled by her own will. Her body enthusiastically xplodesEin front of the audience covered with streams of sweat and possessed by something supernatural. The dancing is accompanied by a music which is a mixture of classical piano and cello together with Japanese ethnical tune. The dancers change their costumes several times according to each part of the performance. We are rather attracted by those who danced clad in an oriental under-wear and moved with bodily convulsions which sometimes give us some unpleasantness. Near the finale of this part two male nude dancers completely covered with white powder conduct an exceedingly exquisite movements. They gallop from the bottom of chaos up to the height of concord in an instant. We are grasped by the expressions of their eyes. We are magnetically attracted by their marvelous performances. We are unable to see otherwise than her facial expressions.

One of the most impressive scenes was that of a serpent decorated with lots of bells.The musical accompaniment and stage lighting absolutely accord with the dancing. It is almost unbelievable Kayo Mikami 46 year-old Japanese dancer equipped with enviable vigorousness and incessant movements always keeps us intoxicated with absolute rapture for such long hours. @@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@Spain@uABC£ September 6, 1996@ Africa Calvo

JAPANESE Butoh is one of those strange and hauntingly beautiful art forms which Western audiences can appreciate without necessarily understanding in any detail, because the skills involved are apparent|or at least can be guessed at|even when the meaning itself is not clear.

Bat watching Kayo Mikami, as she creates her visual poem of painful experience, hope, and ultimate joy, you can easily recognize the intensity of feeling and be drawn into her spiritual journey even if the particular significance of certain colors or props slip by, unregistered.

Mikamifs ability to hold an expressive stillness is enthralling. But when she goes on to shatter that pool of grief or meditative calm, with juddering spasms (where flailing, thrashing limbs look as if they might wrench free of their very sockets) you glimpse the true extent of her control over every muscle, every movement. For there is a total orchestration of gesture, a complete embodiment of reaction, of mood, of thought, which suggests not so mach a performance, but a state of being. And though she is the compelling force at the center of the piece, this is not a solo work : two male dancers from Torifune Butoh sha also take part, their exuberant energies a foil for her composure.@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@iEnglanduThe Heraldv Mary Brennan, 20 Aug.1999j

Samuel Beckett Theatre

TCD

The visiting Japanese Butoh group Torifune butoh-sha gave Irish theatre practitioners

an exceptional development opportunity in taking them through a three-week training period to perform this programme. Dating from a controversial performance in 1959, Ankoku Butoh (Dance of Darkness) arose as post-second World War Japanfs amalgamation of and defiant response to the varying influences and developments in its society. As well as 20th century dance traditions (before the war, many Japanese performing artists had visited Europe and learned classical and modern dance techniques), it incorporates traditional Japanese theatre techniques from the Noh, Kabuki, and Bunraku to create an enigmatic art form that resists the pure reason and quantifiable thought on which we Westerners rely and pride ourselves.

The first piece in the programme, Kenka, presented nearly one and a half hours of mesmeric movement. The leading dancer of the company, Kayo Mikami, gave a performance that left little doubt as to the nature of purgatory. Portraying a woman who has died young and still pines for her child on Earth, Mikami superbly displayed a lynchpin of Butoh: that transformation of the self into that which is portrayed, with the act of metamorphosis being the key, the mindfs movement into a different state.In the various sections of the piece, Mikami displayed utmost physical and mental control in a convincing performance as a body animated not by life but by grief. Her dance proceeded at times achingly slow, as though she were a statue being shifted mechanically across the stage, and sometimes wildly, with movement seemingly uncontrolled. Her white face and body paint – traditional in many forms of Butoh – as well as her unconventional dancing gave the eerie sense of a corpse that could not die, powered by something larger and stronger than life.

In Kandachime, Irish performing artists joined the other members of the company to present a piece inspired by the Kandachime, wild horses living in the coldest regions of Japan who survive the harshest circumstances. Apart from the slow, slow movement and the sometimes rigorously stylised, sometimes chaotic choreography and stage direction, some of the most striking elements of the piece were the extreme facial expressions and contortions presented by the actors. The guests did well here, newly introduced to the art form, but the Japanese company members defy description in their ability, with the help of white makeup, to create a mercurial, mask-like visage – even their faces could dance.

I was surprised that apparently no dance professionals took part in this superb training and performing opportunity. Witnessing such a performance is a transformational experience and I expect, like homeopathy, will continue to alter consciousness and perception long after the actual dosage. I canft imagine what it must be like to be embroiled in it. Although it requires some sticking power, anyone seriously interested in the performing arts should see and explore this

iIreland@The Irish Times@Christine Madden ,21 Feb 2004 j

|

eBreathtaking visions of withering corpses, each infinitely sad and uniquee |

Dublin was treated to a rare performance event with the visit of Japanese Butoh dance company Torifune Butoh-sha. The company worked at the Samuel Beckett Centre for three weeks offering an intense workshop to 16 Irish Theatre practitioners, including Trinity drama students, and then gave a performance consisting of two pieces, Kenka and Kandachime, the latter of which featured the Irish performers. The movement language of Butoh is developed from the traditional Noh theatre of Japan. It was born after the 2nd World War out of a search for a modern Japanese identity, and as a reaction to the unprecedented horrors of the war.

Kenka started with a lengthy episode of a barely moving female figure traversing eternally slowly across the stage, and back again. This was the virtuoso Kayo Mikami, who trained with the creator of Butoh, Tatsumi Hijikata.During this a couple of people left the auditorium and sighs of impatience could be heard, for myself too it took a while to accept the unfamiliar movement language. The following four sequences had different rhythms, and Mikami was counterpoised at times by other performers. Kenka is described as the story of a dead mother who wanders between this life and the next in search of her baby, a theme echoing the Noh canon. Though the narrative did not come across to one uninitiated like myself, the images evoked were powerfully resonant nonetheless, like a woman clad rainbow-coloured rags with a huge parasol, or in bright red struggling with her body like one being born. In the end I would have loved to watch this piece to learn to appreciate it more fully.

The second piece, Kandachime, was more accessible, as with 16 performers there was simply more to look at. A typical visual image in Kandachime was a group of people moving in unison like listless waves with one figure traversing the group, and one completely still. Sound was an important element in creating shifts of mood in both dance pieces, varying from abstract sound-scape to eindustrialf and classical music and old pop-song.

A Butoh dancer aims at letting go of any sense of self, with the body as a fragile, empty shell. At times the whole body or parts of it freeze, die, then fight to break into movement again. The dancer should not communicate their own persona or any idea at all, but simply act as a vessel for each individual audience membersf subjective feelings, thoughts and reactions that it inspires. This poetic freedom of interpretation is helped by the costumes, which bear no reference to everyday reality, often leaving the body almost completely exposed. In Kayo Mikamifs performance the pure presence of the body, devoid of an ego, was staggering. Many Irish performers, too, managed to just let their soulless body express what it would and the audience saw some breathtaking visions of withering corpses, each infinitely sad and unique in its precious fragility, contrary to what the logic of war would have us believe.

(Riikka Jokelainen, Trinity News, 2nd March 2004)